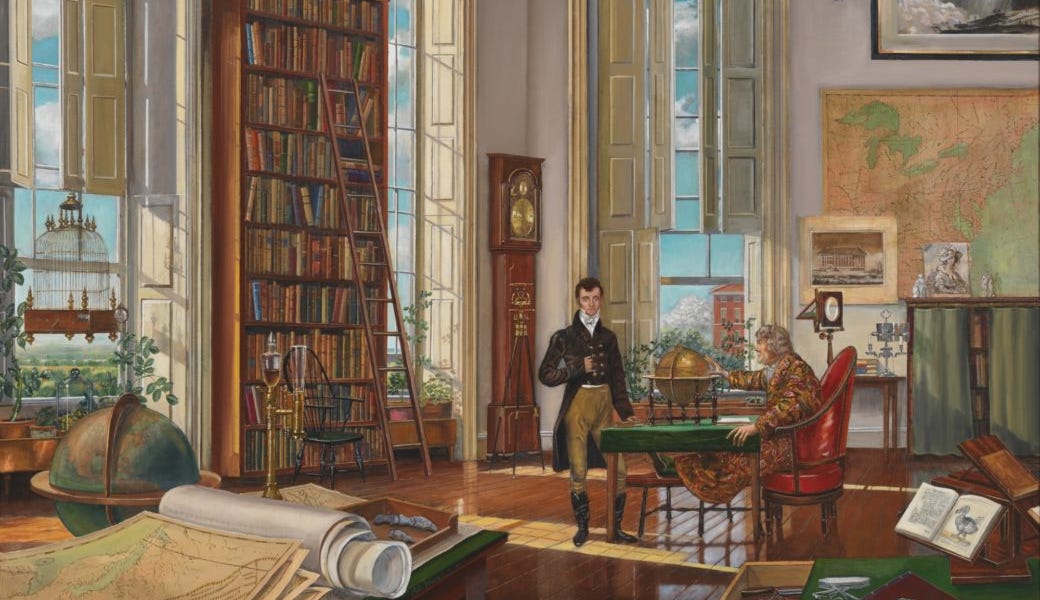

Jefferson and America's Lost Idea: Natural Aristocracy

Aristotle’s fundamental assumptions, in his Politics, are very different from those of any modern writer. The aim of the State, in his view, is to produce cultured gentlemen—men who combine the aristocratic mentality with love of learning and the arts.

Bertrand Russell • History of Western Philosophy

The libertarians were different. They slipped more easily into the American stream. In their insistence on freedom they could claim to be descendants of Locke, Jefferson, and the classical liberal tradition. Some of them interpreted the Constitution as a libertarian document for individual and states rights under a limited federal government, not a

... See moreGeorge Packer • Last Best Hope: America in Crisis and Renewal

The new ideology of meritocracy competed with two alternative notions of social organization: the egalitarian principle, with its call for complete equality in the distribution of goods between humans; and the hereditary principle, with its belief that titles and posts (and partridge shoots) should be automatically transferred to the children of th

... See more